Sir Jack Hayward (1923-2015)

Sir Jack Hayward (1923-2015) has taken an active interest in the Assault Glider Trust and is a major sponsor of the restoration of both the C47 Dakota and the Waco CG-4 (Hadrian) assault glider. The glider will be displayed in the markings of one of the aircraft flown by Sir Jack during his World War II service in Burma.

In September 2005, Sir Jack attended the Burma Commemoration Service and Open Weekend at RAF Shawbury to see “his” glider.

"When you go home, tell them of us and say, for your tomorrow, we gave our today" John Maxwell Edmonds (1875-1958)

Sir Jack Hayward OBE was born in Wolverhampton, England, in 1923 and attended Stowe school in Buckingham, England.

In 1941, at the age of 18, he joined the Royal Air Force. He soon obtained his wings and he trained in Canada and America before being posted to India where he volunteered as a glider pilot for the war against the Japanese. He flew missions over India and Burma and was demobilised as a Flight Lieutenant in 1946.

Sir Jack first arrived in Grand Bahama in 1956, when he became a Vice President of The Grand Bahama Port Authority and helped promote the development of Freeport. His father, Sir Charles Hayward, began the Hayward involvement with the Bahamas in the 1950s. This was taken over by Sir Jack, who developed Freeport in the Bahamas, a very successful development that he continues to play a role in.

Among his benevolent projects he bought Lundy Island, off the coast of Devon, for the National Trust in 1969, and funded the rescue of the first iron ship, Brunel's S.S. Great Britain, from the Falkland Islands so that it could be restored as a National Treasure. It is now berthed in Bristol where he was given the freedom of the city in May, 2003. Also, Sir Jack donated funds for a hospital in Port Stanley following the Falklands War, and made a hefty donation to the building of the first MCC indoor cricket school. For his achievements, he was awarded the OBE in 1968, and was knighted in 1986.

671 Sqn Crest

Flying Officer Jack Hayward RAF (front row, 4th from the left) with other members of No 671 Squadron Royal Air Force, Belgaum, India 1945

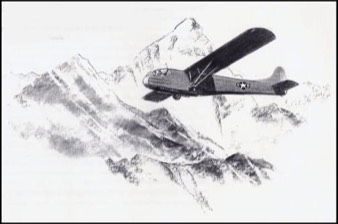

Above: “High Tow” by Frank Wootton. Hadrian (Waco) gliders of No 671 Sqn RAF in action, Assam 1944/45 © Mrs. V Wootton

Recollections of wartime service in India and Burma by Sir Jack Hayward OBE

All drawings on this page by Frank Wootton © Mrs. V. Wootton

“We were surely unique in the history of the RAF to be a squadron of both Glider Pilot Regiment chaps and RAF aircrew commanded by an Army Major.” Jack Hayward (1923-2015)

“I do think that Colin Smith and I were the first and maybe only crew to loop a Wacker (Waco). Two or three crews were chosen or delegated (I don't know which) to go to Panagarh, which was about 200 miles North West of Calcutta.

It was an American air force base with all the luxuries that the Americans had, such as white Red Cross girls serving coffee and doughnuts on the flight line; much better food than we had had for years and the usual American coffee shop and PX. At the base, CG4As were arriving in crates from the States, being unpacked and assembled. Our job was to test fly the gliders after they had been assembled. We were towed up to I think, 5,000ft and then we stalled them and generally used all the controls that we could. I remember to our surprise that the seats were bucket type and we were told to wear parachutes, which fitted into the seat and which we sat on.

I chatted up one of the mechanics one day who was assembling the gliders and asked him if he thought they could be looped and at what speed he thought it would be possible. He said he had never heard of anyone looping a glider and that the wings might come off. For the life of me I can't remember what speed he recommended we should get up to before we pulled her out of the dive.

Anyway, I checked with Colin that he was game to have a go. I asked the tow plane pilot to take us up to about 7,000ft and after making sure that the glider was in good shape, we put her into a dive and she went over beautifully. I may be exaggerating through old age, but I am certain we were so elated that we did another one."

"Both Colin Smith, my co-pilot, and I have lost our log books, but it was certainly at Fatehjang, near Rawalpindi and I am pretty sure it was on 16th November 1944 that Colin and I nearly saw the end of our days. We had started training on Waco Hadrians and the latter were loaded with sandbags which were strapped down, the weight of these presumably simulating a glider full of troops. I think we had to land on a 'bullseye' in the middle of the runway and we were being towed by Dakotas which had been instructed to take us on single tow to 1,000ft before we did our own cast-off over the end of the runway.”

“As our glider was being hitched up to the tow rope, Colin did the usual check of the two trimming wheels above his head. I think the procedure was to turn them fully one way and then fully the other and then settle for a halfway point before take-off. I did the usual check of rudder, pedals and stick backwards and forwards and the wheel turned to its extremities and I looked out of the canopy and saw that the control surfaces were moving accordingly. While we were being hitched up, the rear door of the Dakota opened and three members of the crew jumped out, ran towards us and yelled and asked if they could have a ride as they had never flown in a glider Colin went back over the sandbags, opened the door and let them in and I told them to sit in the middle of the fuselage.”

“When we started down the runway and gained some speed, I pulled back on the control wheel, which I found to be much more hard work than usual However, after some heaving we were airborne and helped the tail of the Dakota get up. When the Dakota was fully airborne and the wheels were up, I was still straining to hold the wheel back so after we made the first turn, I asked Colin to check the trim and I seem to remember him turning the trim wheels to their extremities both ways but with no improvement to the flying of the glider I asked him to help hold the wheel as we pulled the pin out of the control column and both of us heaved the wheel over to him and replaced the pin. He agreed with me that it was hard to hold the glider in position without exerting a lot of pulling back on the wheel While Colin had control of the glider, I tried the trim wheels myself to both their limits and Colin agreed that it made no difference.”

“As we were going into the final leg before casting off, we both strained on the wheel to get it back to my side of the cockpit We put the pin back in place and I remember commenting to Colin that to cap it all the Dakota had taken us to 1,200ft instead of 1,000ft. When I thought we were in the right position to release, I asked Colin to pull the lever Instantly, as soon as we lost the forward speed, the wheel and control column were yanked out of my hands and hit the perspex roof of the canopy. The nose dropped immediately and Colin, who was not strapped in, fell to the bottom of the canopy.”

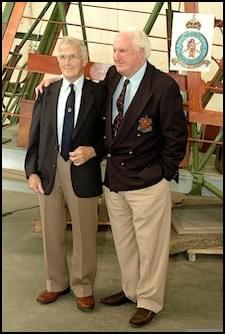

Sir Jack and co-pilot Colin Smith (on left) visit the Trust during the Burma Open Weekend in September 2007

“I reached forward and got the wheel back into my hands and pulled as hard as I could. By this time, we were in a vertical dive and I was standing on the rudder pedals! Colin somehow scrambled back into his seat, with our speed increasing dramatically. With the initial drop of the nose, the sandbags had shifted and the three members of the Dakota crew were thrown into the backs of our seats. This of course did not help the distribution of weight.

I remember quite clearly, whilst fighting to pull the glider out of the dive, thinking that death was going to be quick and painless. There seemed no way out. Nothing was giving way and the nose was not coming up. The dive was vertical and God knows what the speed was. By sheer luck we were diving into a deep nullah when suddenly something snapped and the nose came up. It was a miracle that the wings did not pull off with the strain put on them at that speed. We must have wallowed into the nullah and touched the sparse scrub.

With the speed we had, we rose fairly quickly to about 500ft and actually we had the speed and height to make a turn and come back on to the runway. However our instructions were to always fly straight ahead and look for a suitable landing spot. This was not easy as it was rocky, hilly terrain. As we flew straight ahead, gradually losing speed, Colin spotted a flattish table-top on a hillock ahead of us and I managed to prevent a stall and dropped hard onto this flat but rocky small area. The wings collapsed downwards. The inside of the fuselage was like being in a sandstorm with the sandbags leaking, having broken their straps."

"When details of the flight were posted and we were briefed on the route etc. I conceived the idea of flying through the blister hangar that was on the airfield. However, I took the precaution of having the erks put a Tiger in the flying position inside the hangar and then I calculated what distance I would have on either side of me, presuming that I would be flying at a little less than five feet off the deck. There was not much clearance between the wingtips and the inside of the hangar. I also checked that the hangar was clear of obstructions and that the erks knew what I intended to do so that they did not accidentally leave obstructing equipment in my flight path through the hangar. Finally, we pushed the Tiger through the hangar in the flying position.”

“We took off next morning early to avoid the bumpiness that developed as the day progressed. I was first off and at about 300 feet lined myself up on to the hangar and set the aircraft into a controlled shallow dive. It was all over in a matter of seconds and everything went as planned but what I had not been prepared for was the noise! The Tiger Moth only has a Gipsy Major engine, one could hardly say that it produced a roar, but in the confined space of that hangar, with the engine sound hitting the hangar wall and being deflected back to the cockpit, the noise was most disturbing."

Extracts from “No 671 Squadron RAF, a wartime history” reproduced with kind permission of the publisher Richard Lucraft Ltd and Sir Jack Hayward OBE. © Mr Antony Day CM CD